If you visit a number of parks and forests in Ohio, you will occasionally come across a structure built of sandstone blocks that resembles the bottom of a pyramid. A few of these are intact; many are just ruins overgrown with plants. These are the remnants of blast furnaces built in the early nineteenth century. But what are they doing out in the middle of the forest?

In the above photo the topmost, wooden building is the bridge loft. Workers in the bridge loft dropped raw materials through the floor into the furnace. The stone structure beneath it is the iron-producing furnace. The molten iron actually poured out onto the dirt floor of the structure with open walls to the right. The wooden building to the left housed a steam engine that blew hot air into the iron-producing furnace.

Early Ohio settlers started building blast furnaces in Ohio at the beginning of the 19th century. The Hanging Rock 1 Iron Region extended from northern Kentucky through the Hocking Hills of Ohio. This region had an abundance of iron ore, limestone, and trees to make charcoal… everything required to make iron.

The blast furnace was a truncated pyramid of stone. It was usually placed adjacent to a hill-side. A building would extend from the top of the hill to the top of the furnace. From the building up above, the following raw materials were dumped into the blast furnace.

- Iron ore from local, hand-dug surface mines

- Charcoal (from partially burnt trees) acted as a fuel source, and produced carbon monoxide which acted as a reducing agent to turn the iron ore into iron

- Limestone to dissolve and bind the impurities from the ore

In the photo above the peak of the roof is open with another mini-roof covering the opening. The furnace generated a lot of hear and the opening at the top of the roof allowed some of the heat to escape. The iron-producing furnace is beneath this wooden structure at the end farthest from the viewer. The chimneys belong to the blast furnace that is near the front of the building. Hot air from the blast furnace above was blown into iron-producing furnace below by a steam-powered engine.

The heat from the furnace above was blasted into the iron-producing furnace below the bridge loft by a steam-powered engine.

During a 12 hour period, men had to dump 57,600 pounds of iron ore, 19,000 pounds of limestone, and 800 bushels of charcoal through that iron door in the floor of the bridge loft.

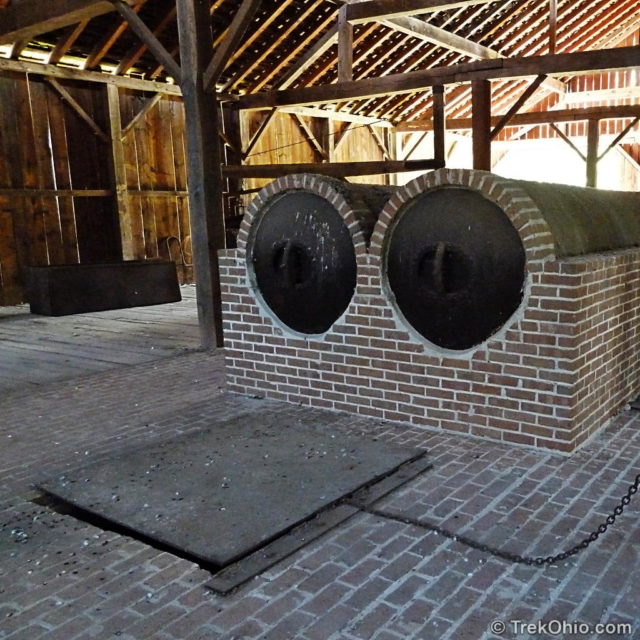

Back when the furnace was functioning, the floor that’s pictured above was covered with a thick layer of sand. Workmen used wooden molds to make depressions in the sand. The molten iron poured down a central channel that ran down the middle of this floor. Outlets to the side of the channel allowed the molten iron to pour into the sand depressions. Because the way the iron-filled depressions where connected to the central channel, it reminded people of the way that piglets line up to suckle from their mother, so this iron came to be called pig iron. After the iron cooled and was collected, the flywheel was used to pull the slag out of the furnace.

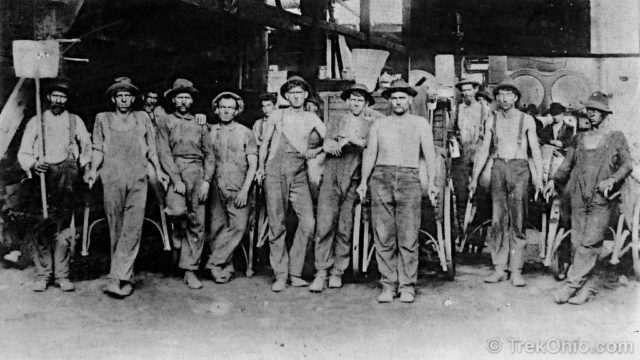

In the above vintage photo, the furnace is to the rear. The channel for the molten iron is to the left. In the foreground you can still see depressions in the sand into which the molten iron had poured forming the “pigs” that gave “pig iron” its name.

A steam engine in the building would force air via duct work (called tuyeres) into the blast furnace to make the charcoal burn hotter. A later development involved preheating the air (‘hot blast’ furnaces) to make the furnace more efficient. The furnaces were sufficiently hot that the extracted iron would liquefy into molten iron. A layer of molten slag – limestone with dissolved impurities would form on top of the iron.

Once the ore had been processed into iron (called smelting), workers would open a channel at the base of the furnace. Molten iron would pour through the channel into molds called pigs 2. Once cooled, the resulting product is known as pig iron. Next the slag would be removed via another channel and allowed to cool. Initially the slag was dumped in a pile called a slag heap. Subsequently, uses were found for slag – for instance, in making cement. The pig iron was then transported to manufacturing centers via horse and wagon, or possibly rail. Eventually 69 furnaces were built in southern Ohio; these furnaces supplied iron for America’s emerging manufacturing industry.

Many of the owners of the iron furnaces were staunch abolitionists. The furnace buildings were an important component of the Underground Railroad used by escaped slaves in their quest for freedom. During the civil war, Ohio was a major supplier of iron used by the Union army which gave the Union an industrial edge over the Confederacy.

Eventually higher grade sources of ore were found (in northern Michigan among other places), and the technology of iron making (and by then steel making) advanced rendering the southern Ohio furnaces obsolete and uneconomical. By the early 20th century, the furnaces had been shut down or abandoned.

Today most are mysterious ruins in the forest. A few, such as the furnaces at Lake Hope and Lake Vesuvius, are intact. Buckeye Furnace alone has been restored by the Ohio Historical Society. Besides seeing the stone furnace, you can see the supporting buildings and infrastructure that were used in operating the furnace.

The above photo shows the ruins of the iron furnace at Lake Vesuvius. Now that you’ve seen the structure that has been replaced over Buckeye Furnace, you can imagine a similar one over Vesuvius Furnace.

Because of the vegetation in the above photo, you can’t see that there is a hill behind this furnace, too. A bridge loft would have extended from the hill behind Hope Furnace until it topped the furnace, so workers could drop raw materials down into the furnace similar to the layout of the restored Buckeye Furnace complex.

Footnotes

- Hanging Rock is the name of a small town on the Ohio river that was the site of an early blast furnace. It is named after a rock that was an underwater obstruction on the Ohio River, which would hang up local barges.

- In case you are wondering why the molds that received the molten iron were called “pigs,” apparently the way they were lined up to receive the iron reminded these rural people of baby pigs lined up to nurse from their mother.

Additional information

- TrekOhio: Jackson County Parks & Nature Preserves — This is the county where Buckeye Furnace is located; check it out for links to official sites, and for information on nearby parks and preserves.

- TrekOhio: Lake Hope State Park — Includes the ruins of Hope Furnace

- TrekOhio: Wayne National Forest: Lake Vesuvius in the Ironton Unit — Includes the ruins of Vesuvius Iron Furnace

- TrekOhio: Vinton Furnace State Experimental Forest — Includes the ruins of Vinton Iron Furnace, plus the world’s only remnants of a Belgium coke oven.

- School teacher builds blast furnace in 2002

- Much more about Buckeye Furnace

- How an old iron furnace (Mt. Olive) worked

- Condition of Old Ohio Blast Furnaces

- List of Ohio Furnaces

- Historic Pictures of Vesuvius Furnace

- Ohio History Connections: Buckeye Furnace

Location

- Address: 123 Buckeye Park Rd. (T–167), Wellston, Ohio 45692

- GPS Coordinates: 39.0562152, -82.457823

- Google Maps: View on map or get directions

See Ohio Historical Society’s page for the Buckeye Furnace and click on the link for Hours and Admission to make sure that the museum is open before you go.

More on Ohio's Industrial History

Do you know much about the hiking trails there?

No, we just visited the historical site.

Really fascinating… Love how you incorporate the vintage photos. Really gives a sense of history and place.